15. Compiling your game¶

lmost as rarely as an alchemist producing gold from base metal, the compilation process turns your source file into a story file (though the more usual outcome is a reproachful explanation of why – again – that hasn’t happened). The magic is performed by the compiler program, which takes your more or less comprehensible code and translates it into a binary file: a collection of numbers following a specific format understood only by Z-code interpreters.

On the surface, compilation is a very simple trick. You just run the compiler program, indicating which is the source file from which you wish to generate a game and presto! The magic is done.

However, the ingredients for the spell must be carefully prepared. The compiler “reads” your source code, but not as flexibly as a human would. It needs the syntax to follow some very precise rules, or it will complain that it cannot do its job under these conditions. The compiler cares little for meaning, and a lot about orthography, like a most inflexible teacher; no moist Bambi eyes are going to save you here.

Although the spell made by the compiler is always the same one, you can indicate up to a point how you want the magic to happen. There are a few options to affect the process of compilation; some you define in the source code, some with switches and certain commands when you run the program. The compiler will work with some default options if you don’t define any, but you may change these if you need to. Many of these options are provided “just in case” special conditions apply; others are meant for use of experienced designers with advanced and complex requirements, and are best left (for now) to those proficient in the lore.

Ingredients¶

If the source file is not written correctly the compiler will protest, issuing either a warning message or an error message. Warnings are there to tell you that there may be a mistake that could affect the behaviour of the game at run-time; that won’t stop the compiler from finishing the process and producing a story file. Errors, on the other hand, reflect mistakes that make it impossible for the compiler to output such a file. Of these, fatal errors stop compilation immediately, while non-fatal errors allow the compiler to continue reading the source file. (As you’ll see in a minute, this is perhaps a mixed blessing: while it can be useful to have the compiler tell you about as many non-fatal errors as it can, you’ll often find that many of them are caused by the one simple slip-up.)

Fatal errors

It’s difficult – but not impossible – to cause a fatal error. If you indicate the wrong file name as source file, the compiler won’t even be able to start, telling you:

Couldn't open source file filename

If the compiler detects a large number of non-fatal errors, it may abandon the whole process with:

Too many errors: giving up

Otherwise, fatal errors most commonly occur when the compiler runs out

of memory or disk space; with today’s computers, that’s pretty unusual.

However, you may hit problems if the story file, which must fit within

the fairly limited resources specified by the Z-machine, becomes too

large. Normally, Inform compiles your source code into a Version 5 file

(that’s what the .z5 extension you see in the output file

indicates), with a maximum size of 256 Kbytes. If your game is larger

than this, you’ll have to compile into Version 8 file (.z8), which

can grow up to 512 Kbytes (and you do this very simply by setting the

-v8 switch; more on that in a minute). It takes a surprising amount

of code to exceed these limits; you won’t have to worry about game size

for the next few months, if ever.

Non-fatal errors

Non-fatal errors are much more common. You’ll learn to be friends with:

Expected something but found something else

This is the standard way of reporting a punctuation or syntax mistake. If you type a comma instead of a semicolon, Inform will be looking for something in vain. The good news is that you are pointed to the offending line of code:

Tell.inf(76): Error: Expected directive, '[' or class name but found found_in

> found_in

Compiled with 1 error (no output)

You see the line number (76) and what was found there, so you run to the source file and take a look; any decent editor will display numbers alongside your lines if you wish, and will usually let you jump to a given line number. In this case, the error was caused by a semicolon after the description string, instead of a comma:

Prop "assorted stalls"

with name 'assorted' 'stalls',

description "Food, clothing, mountain gear; the usual stuff.";

found_in street below_square,

pluralname;

Here’s a rather misleading message which maybe suggests that things in our source file are in the wrong order, or that some expected punctuation is missing:

Fate.inf(459): Error: Expected name for new object or its textual short name

but found door

> Object door

Compiled with 1 error (no output)

In fact, there’s nothing wrong with the ordering or punctuation. The

problem is actually that we’ve tried to define a new object with an

internal ID of door – reasonably enough, you might think, since the

object is a door – but Inform already knows the word (it’s the name

of a library attribute). Unfortunately, the error message provides only

the vaguest hint that you just need to choose another name: we used

toilet_door instead.

Once the compiler is off track and can’t find what was expected, it’s common for the following lines to be misinterpreted, even if there’s nothing wrong with them. Imagine a metronome ticking away in time with a playing record. If the record has a scratch and the stylus jumps, it may seem that the rest of the song is out of sync, when it’s merely a bit “displaced” because of that single incident. This also happens with Inform, which at times will give you an enormous list of things Expected but not Found. The rule here is: correct the first mistake on the list and recompile. It may be that the rest of the song was perfect.

It would be pointless for us to provide a comprehensive list of errors, because mistakes are numerous and, anyhow, the explanatory text usually indicates what was amiss. You’ll get errors if you forget a comma or a semicolon. You’ll get errors if your quotes or brackets don’t pair up properly. You’ll get errors if you use the same name for two things. You’ll get errors – for many reasons. Just read the message, go to the line it mentions (and maybe check those just before and after it as well), and make whatever seems a sensible correction.

Warnings

Warnings are not immediately catastrophic, but you should get rid of them

to ensure a good start at finding run-time mistakes (see Debugging your game). You

may declare a variable and then not use it; you may mistake assignment and

arithmetic operators (= instead of ==); you may forget the comma

that separates properties, etc. For all these and many other warnings,

Inform has found something which is legal but doubtful.

One common incident is to return in the middle of a statement block, before the rest of statements can be reached. This is not always as evident as it looks, for instance in a case like this:

if (steel_door has open) {

print_ret "The breeze blows out your lit match.";

give match ~light;

}

In the above example, the print_ret statement returns true after the

string has been printed, and the give match ~light line will never

happen. Inform detects the fault and warns you. Probably the designer’s

intention was:

if (steel_door has open) {

give match ~light;

print_ret "The breeze blows out your lit match.";

}

Compiling à la carte¶

One of the advantages of Inform is its portability between different

systems and machines. Specific usage of the compiler varies accordingly,

but some features should be in all environments. To obtain precise

information about any particular version, run the compiler with the

-h1 switch – see Switches.

Often the compiler is run with the name of your source file as its only

parameter. This tells the compiler to “read this file using Strict mode and

from it generate a Version 5 story file of the same name”. The source file

is mostly full of statements which define how the game is to behave at

run-time, but will also include compile-time instructions directed at the

compiler itself (although such an instruction looks a lot like a

statement, it’s actually quite different in what it does, and is

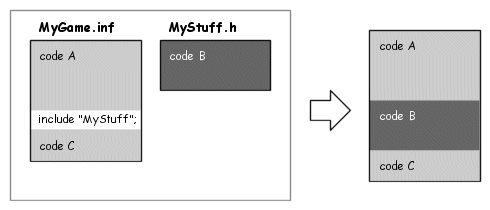

known as a directive). We have already seen the Include

directive:

Include "filename";

When the compiler reaches a line like this, it looks for

filename – another file also containing Inform code – and

processes it as if the statements and directives included in

filename were in that precise spot where the Include

directive is.

In every Inform game we Include the library files Parser,

VerbLib and Grammar, but we may Include other files. For

example, this is the way to incorporate library extensions contributed

by other people, as you saw when we incorporated pname.h into our

“Captain Fate” game.

Note

On some machines, a library file is actually called – for example –

Parser.h, on others just Parser. The compiler automatically

deals with such differences; you can always type simply Include

"Parser"; in your source file.

As you grow experienced in Inform, and your games become more complex, you may find that the source file becomes unmanageably large. One useful technique is then to divide it into a number of sections, each stored in a separate file, which you Include into a short master game file. For example:

!============================================================================

Constant Story "War and Peace";

Constant Headline

"^An extended Inform example

^by me and Leo Tolstoy.^";

Include "Parser";

Include "VerbLib";

Include "1805";

Include "1806-11";

Include "1812A";

Include "1812B";

Include "1813-20";

Include "Grammar";

Include "Verbski";

!============================================================================

Switches¶

When you run the compiler you can set some optional controls; these are called switches because most of them are either on or off (although a few accept a numeric value 0–9). Switches affect compilation in a variety of ways, often just by changing the information displayed by the compiler when it’s running. A typical command line (although this may vary between machines) would be:

inform source_file story_file switches

where “inform” is the name of the compiler, the story_file is

optional (so that you can specify a different name from the

source_file) and the switches are also optional. Note that

switches must be preceded by a hyphen -; if you want to set, for

instance, Strict mode, you’d write -S , while if you want to

deactivate it, you’d write -~S. The tilde sign can, as elsewhere,

be understood as “not”. If you wish to set many switches, just write them

one after another separated by spaces and each with its own hyphen, or

merge them with one hyphen and no spaces:

inform MyGame.inf -S -s -X

inform MyGame.inf -Ssx

Although there’s nothing wrong with this method, it isn’t awfully convenient should you need to change the switch settings. A more flexible method is to define the switches at the very start of your source file, again in either format:

!% -S -s -X

!% -Ssx

Normally, all switches are off by default, except Strict mode

(-S), which is on and checks the code for additional

mistakes. It’s well worth adding Debug mode (-D), thus making the

debugging verbs available at run time. This is the ideal setting while

coding, but you should turn Debug mode off (just remove the -D)

when you release your game to the public. This is fortunately very easy to

check, since the game banner ends with the letter “D” if the game was

compiled in Debug mode:

Captain Fate

A simple Inform example

by Roger Firth and Sonja Kesserich.

Release 3 / Serial number 040804 / Inform v6.30 Library 6/11 SD

Switches are case sensitive, so you get different effects from -x

and -X. Some of the more useful switches are:

-

-S¶

-

-~S¶ Set compiler Strict mode on or off, respectively. Strict mode activates some additional error checking features when it reads your source file. Strict mode is on by default.

-

-v5¶

-

-v8¶ Compile to this version of story file. Versions 5 (on by default) and 8 are the only ones you should ever care about; they produce, respectively, story files with the extensions .z5 and .z8. Version 5 was the Advanced Infocom design, and is the default produced by Inform. This is the version you’ll normally be using, which allows file sizes up to 256 Kbytes. If your game grows beyond that size, you’ll need to compile to the Version 8 story file, which is very similar to Version 5 but allows a 512 Kbytes file size.

-

-D¶

-

-X¶ Include respectively the debugging verbs and the Infix debugger in the story file (see Debugging your game).

-

-h1¶

-

-h2¶ Display help information about the compiler.

-h1produces innformation about file naming, and-h2about the available switches.

-

-n¶

-

-j¶ -ndisplays the number of declared attributes, properties and actions.-jlists objects as they are being read and constructed in the story file.

-

-s¶

-

-~s¶ Offer game statistics (or not). This provides a lot of information about your game, including the number of objects, verbs, dictionary entries, memory usage, etc., while at the same time indicating the maximum allowed for each entry. This can be useful to check whether you are nearing the limits of Inform.

-

-r¶ Record all the text of the game into a temporary file, useful to check all your descriptions and messages by running them through a spelling checker.

If you run the compiler with the -h2 switch, you’ll find that

there are many more switches than these, offering mostly advanced or

obscure features which we consider to be of little interest to beginners.

However, feel free to try whatever switches catch your eye; nothing you try

here will affect your source file, which is strictly read-only as far as

the compiler is concerned.